To live is to span the gap between the past and future.”

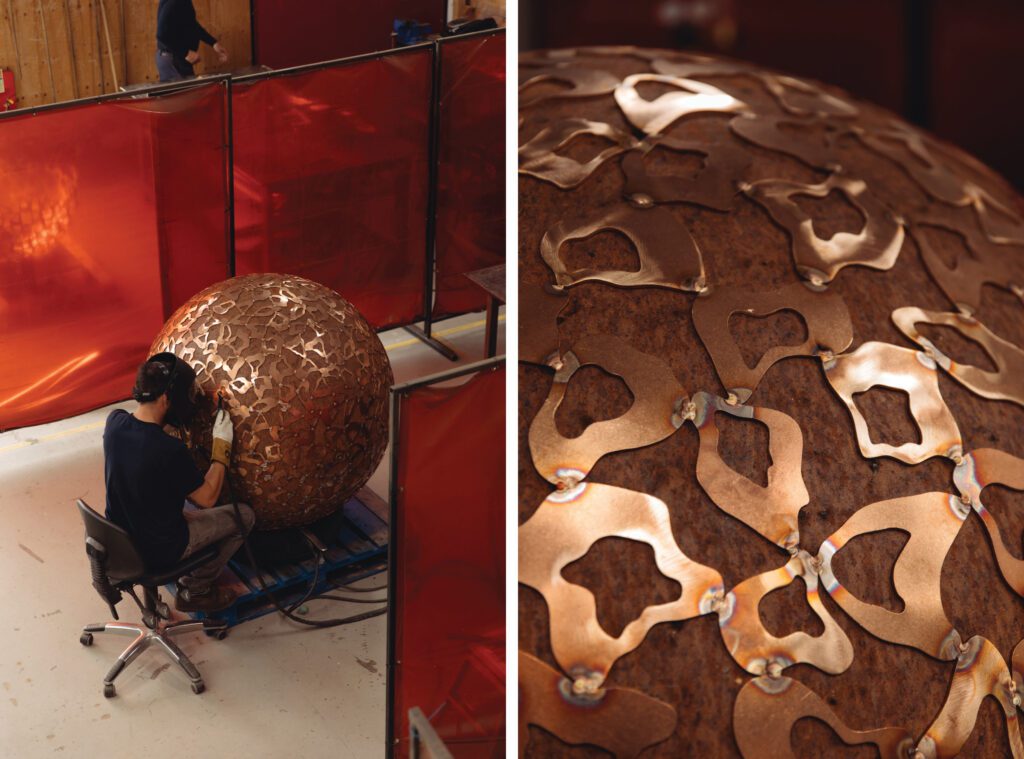

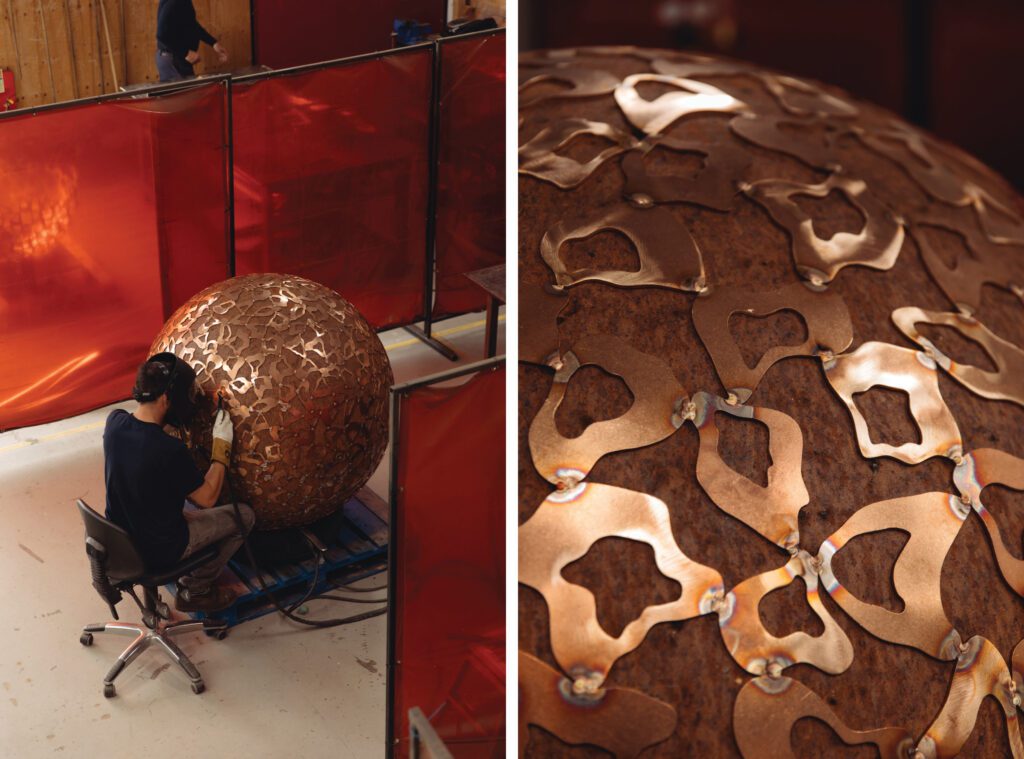

Sitting in his workshop in the idyllic, rolling countryside of Oxfordshire, England, David Harber is keenly aware of his work’s placement on the spectrum of light and time through the ages. It is from this place, this moment in time, that he creates sculpture that’s showcased throughout the world, even within a pocket park at Alys Beach where The Mantle II sits dappled with light and butterfly wings. But each bit of creativity and craftsmanship is rooted in what David finds most essential: time, journey, and light.

THE ORACLES

While David’s own journey to becoming an artist was anything but linear, the wisdom that only time brings makes it clear that it was meant to be, and perhaps in many ways, seemingly foretold.

David attended Dartington Hall School in Devon, England. At fifteen, he left school and began work as a thatcher apprentice, then as a potter. During this time he developed a rudimentary knowledge of shape and form. His career progressed along a path that spanned countries and continents, with each vocation contributing to a vision of creative certainty.

“I was a very competent rock climber, and I managed to do a tiny bit of film work while rock climbing. I heard that there was an expedition to climb unclimbed mountains in Patagonia, so I said, ‘Well, I’ll go.’ I’d never climbed a mountain, and I had never been in snow and ice, but I thought, ‘It can’t be that difficult.’”

“It’s really difficult,” David says wryly. “If someone asks you if you want to be a cameraman climbing unclimbed peaks in Patagonia, just say ‘no’.”

He continues, “I’m really good at leaps of faith. I knew nothing about barges, metalwork or theater, but we decided it would be a really good idea to take a barge and convert it into a theater. My friends were buying them and turning them into traveling hotels. I put my theater barge together and didn’t turn any money, but we had great parties.”

Serendipitously, this decision to handcraft a floating theater would lay the groundwork necessary to pull himself out of dire straits.

“I had this theater on a boat that traveled around Europe performing Shakespeare to the French in Japanese or whatever we were doing at the time.” While this leap of faith had been a large one, it wasn’t returning financial dividends. With personal hardships also rising, he would find that fate would intervene once again, casting new light upon his path.

During that time, David encountered his first sundial through a friend who was an antiques dealer. The friend was traveling back from France, carrying a sundial from the 1920s. The two men had a cup of coffee, and David saw the primitive armillary sphere his friend carried in the back of his van.

“I, then, like a man obsessed, went to Oxford and bought a book about sundials. I measured some sundials in the Museum of History and Science, I bought some metal, and I went back to my cottage. By the end of the day, I had started making one. I had no previous connection to sundials, and I had very, very rudimentary metalworking skills, but I didn’t stop until I’d finished—which took about a week,” says David.

“There I was with my finished product, which was pretty bad if I’m being honest, but the actor Jeremy Irons happened upon me whilst I was working on it, bought it and brought me two months rent. And I was launched, if you will. My bank manager at the time told me that I would run out of people in England who would want to buy a sundial. Thirty years on and we’re still doing it.”

David continues, “Because I never had any formal training, each thing that I did was a complete leap of faith. And when it came to making sculpture, I actually started making sundials because I was obsessed with navigation, I was obsessed with time and the fact that, using metalwork, you could make something that would fulfill both of these elements. There was a beautiful historical, mathematical, esoteric side to them as well. They are oracles. This is what we were known for, particularly in England, for at least twenty years—making sculptures that told the time.”

While his affinity for the ancient timepiece was strong, over time it became clearer that David’s path was almost as if spoken into being by a prophetic word.

He later discovered that one of his ancestors, John Blagrave, was England’s foremost sundial maker and astronomer during the Elizabethan era. David explains, “The sundials are something that really resonate with me because they have an ethereal quality. They take their function from the heavens. Some of them are three or four thousand years old in their concepts. I’ve also invented a few new ones, and considering there’s nothing new under the sun, that’s quite an accomplishment.”

Early in his career, David was asked to restore an old sundial on a very old building. “The building was built in 1514 and when we took the sundial off the wall, on the back of it, scratched in the metal by the man who made it, was the year 1542. So this piece had been up there for nearly 500 years. When I saw that, I decided then and there that whatever we make, in ten generations I want people getting the same pleasure out of it. So we only use marine-grade stainless steel, we use bronze, we use 23¾ karat gold. We use high-quality brass. We don’t make anything that won’t be there in 500 years.” As his vision remains steadfast, legacy has become synonymous with David and his team.

ANCIENT ORIGINS

Though primitive in structure, the truth and steadiness of a sundial is perhaps an anchor for David’s approach to art—and life. “We’re all conscious of time. Though the moment you look at time on a sundial, it becomes a different concept. Time becomes contemplative, inextricable; you can’t beat it, you can’t change it. Time is what it is and has been for billions of years.” David finds comfort and freedom in that consistency, which is why his work as a sculptor began in the study and building of sundials.

“Our ancestors would have had exactly the same feeling about watching the shadow pass. Watching time pass on a sundial is cathartic. You feel almost reassured by it.”

What originated with a primitive sundial has flourished over the past thirty years into a team of discerning makers and designers with an ingenuity that is uniquely British. Even with a global presence, David has maintained a dry, almost self-deprecating wit, and a humble outlook.

He’s entirely without pretense, creating for the sake of bringing joy into the lives of others. “I didn’t go to art college, and I wasn’t always told that I was creative or even making art. And so, my relationship with a piece of sculpture and its production, first and foremost, is centered around my patron.”

David explains, “I’ve always been grateful to be doing what I do, and I have never allowed my ego to get in

the way.”

To David, it is important that the pieces that he makes aren’t necessarily of his own story, but rather, representative of or inspiring to the end-user.

“My pieces can’t have an ego, and neither can I, because what I’m creating is a symbiotic relationship between someone who wants to commission the piece and the artist who wants to produce the piece,” he continues.

He is focused on creating multifaceted artwork that evokes a sense of wonder and delight. Describing his process, he says, “The joy, for me, is to create pieces that have multiple elements to them. A great, meaningful piece either has to have an optical illusion or another narrative running through. Or maybe how it is placed within the environment: on the water and reflecting something, something that creates pause or a

double take.”

Everyone who sees The Mantle that was commissioned for Alys Beach, for example, will ask, “Where is the light?” particularly in the low evening light, because of the way the natural sunlight reflects off of the gold. According to David, “There’s an optical illusion that’s almost magical. As if by magic.”

THE JOY OF ART

David’s passion for inspiring community and relationships through experiential sculpture has led him to lecture on the subject of public art and community development. When the Harber team was approached to create The Mantle II for Alys Beach, an appreciation of the tenets of the community’s commitment to architecture and natural spaces emerged.

“I’m really impressed with the ethos of Alys Beach,” David explains. “They’ve clearly decided to put style and creative content as a benchmark for the core of the place, and once you have a vision, it feeds off itself. The people come for the right reasons. Their sense of aesthetic perpetuates. You can’t quantify art as an embellishment, but once it’s been done, you’re nurturing the souls and spirits of the people who are living there. Nobody has to have art, so the very act of investing in art is an acknowledgment of the value of adding pleasure to life. Above basic needs, creating art becomes very important. I think it’s a necessity.”

David expresses that the process of working with clients is particularly rewarding to him as it invites a conversation to make his art more personal, more evolved. He explains, “I hope to be challenged. Whether it’s a public entity or a private individual, I don’t want to sell them a piece of art, I want to infuse a piece of art to the extent that the viewer will say, ‘Can we involve this? Can we make it more impressive?’”

David continues, “Again, a piece has no ego to it, because all it does is make whatever you’re seeing beautiful. So you can see the reflection of your world, your trees, your light, your sky. That is the perfect example of a piece of sculpture enhancing its environment by honoring its environment.”

As David’s pieces continue to journey around the world, he has given considerable thought about public interaction and the emotion he hopes to evoke with

his sculpture.

He says, “I want people to know that we are creating the piece for them. We don’t have a stock. We don’t have galleries selling our work. Clients have to talk to us, we have to talk to them, and we will be making a piece from scratch for them. I want it to become part of the family. Perhaps the piece has been bought to commemorate twenty years of marriage, it’s been bought to celebrate moving to this new house, opening this new community.”

He continues, “So many of our clients become friends, and if not friends, certainly our ambassadors. I want them to feel a part of our family, because we are a team of forty people. I love thinking about the pieces and how they are interacting with them.”

Reminiscing about past work, David mentions a client whose family commissioned a piece to honor their patriarch. He says, “What they engraved on it was, and I always tear up when I say it, ‘To Peter, on the occasion of his sixtieth birthday. Commissioned in his wife’s name, all his children’s names, all his grandchildren’s names. To whom he has given both roots and wings.’ Peter burst into tears, I burst into tears. That happened twenty years ago and I remember it so strongly to this day. There’s got to be some resonance between the piece, the person, the situation, and the cosmos.”

See the Mantle II in the Alys Beach Butterfly Garden