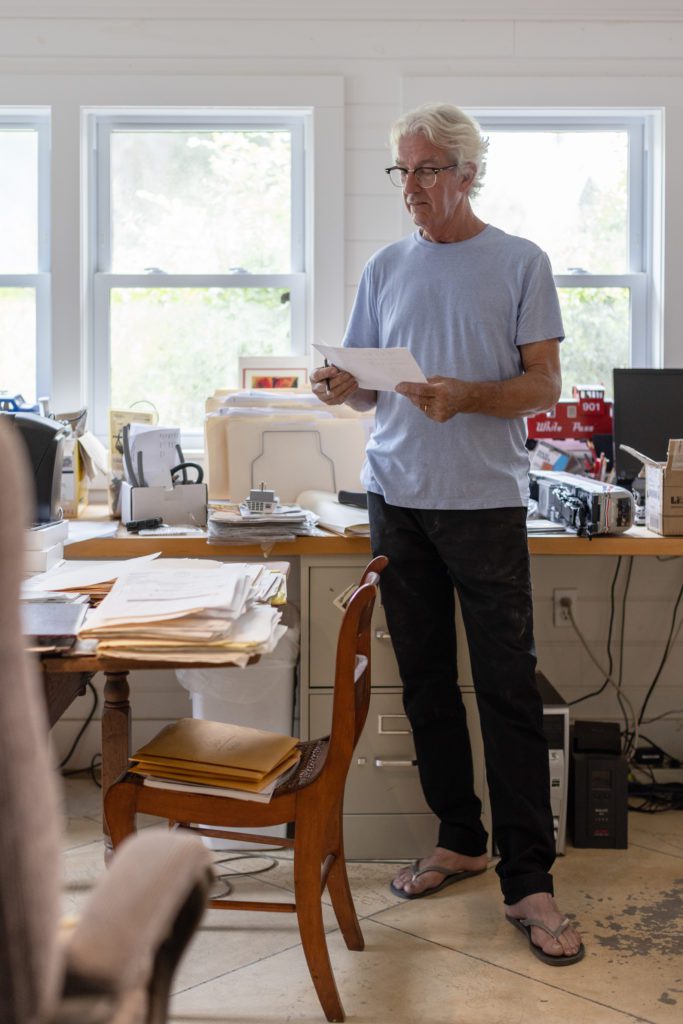

In a backyard workshop in Point Washington, Florida, just a few miles north of Alys Beach, a world of creativity and a lifetime of craftsmanship come together at the hands of David Higgs. With wood or with copper, aluminum or brass, he works to bring great design to life through thoughtful fabrication and innovative technique. An artist by trade, a world traveler by birth, a shop owner with his wife, Geri, and a student of life by upbringing, David holds a multitude of titles by his simple desire to figure out how to make interesting things. His presence is one of humility, the kind that is seasoned with experience and wisdom, and his eye for detail and can-do spirit have resulted in a body of work that has been appreciated around the country and especially by all who know Alys Beach.

He’s a stickler for detail and a job well done. David’s work is a perfect match for Alys Beach, and for years, since he crafted and placed the earliest lot markers in the sandy ground, David, through his company, Meridian Workshop, has worked to help bring a vision of beauty to life.

Meet David Higgs, designer, furniture fabricator, home builder, sign maker, pie baker, a friend of Alys Beach since its inception, and this issue’s Craftsman of Alys Beach.

David’s methodical nature and artful approach to production is a product of both nature and nurture, inspired by his unique upbringing, that challenges not only social norms but also his mind toward innovation and creativity.

Born in Zimbabwe, David, along with his two sisters and one brother, grew up as the son of Methodist missionaries to the semi-arid region of Africa. Through their day-to-day work in the home and in the community, his mother and father taught him ingenuity at an early age. During the day, David’s father, an engineer by trade, worked to build schools throughout the area, while his industrious mother kept the house and encouraged her children to participate in all aspects of making a home. She sewed all their clothes on an old, black Singer machine. His father, in the evenings, finished all the button holes. David and his sister were invited into this practice. When David was 8, his parents taught him to knit, and soon, he was knitting small outfits for his sister’s dolls. His parents shared responsibilities, and they were partners in creating an abundant life for their family and for families in their community by sharing trade skills and employing an imaginative,

resourceful mindset.

“My father really did a lot of things that, at the time and perhaps still today, may have been considered ‘womanly’ things to do. But he and my mother were sure to teach me everything,” David explains.

As a child, David learned about building and stitching, cooking and knitting—anything he was interested in, his parents encouraged him to figure out how to do it. And he did.

When he was 14, his family left Zimbabwe and moved to Nashville, Tennessee, where David finished high school and continued to study art at Peabody at Vanderbilt University. Following his graduate work in design materials from Murray State in Kentucky, he found work building custom furniture for construction firms—jewelry cases for stores and millwork for cabinets, among other projects.

In 1983, after a trip to the Florida Gulf Coast, David decided to build a home along 30A and began what would soon be a legacy of great work in the region.

“I realized all the good sign work was being done in Atlanta,” David says, and he traveled back and forth between his home on 30A and Atlanta, Georgia, where he moonlighted making signage for the likes of IBM and Lockheed Martin for their trade shows.

“Most of the large signage companies had limitations, either budget-wise or in their resources. I knew I could find a way to think outside the box and make things on my own. I knew I could figure out the unique requests that the larger groups couldn’t,” David explains.

“I like the weird things. The interesting projects. I like figuring things out.”

And so began Meridian Workshop, a through-line connecting critical elements and geographies of his life together seamlessly.

Today, David doesn’t consider his work a job. His business is one of creativity, timeliness, and problem solving, and it’s a product of a lifetime of rising to the challenge.

“I’m fortunate to work with incredible designers—Marieanne and Erik of Khoury Vogt Architects and other architects and designers in the Alys Beach landscape—who all bring me wonderful, thoughtful work to execute,” David says.

Alongside KVA, David has been one of the longest-serving artisans that’s shaped Alys Beach.

“I’ve been a part of, well, everything,” he says, laughing as he speaks the words. With humility, he describes creating the letters on the monument sign as visitors approach the Butteries, the original, metal prototype “A” of “Alys Beach” is still mounted on his studio wall.

Since then, he’s created every street sign at Alys Beach, carefully and consistently working with bronze to frame the names of the roads around town. His work is on full display in Town Center, where he’s crafted the signage for many of the merchants, and throughout town as each building is identified by metal signage made by David. He’s also responsible for creating the custom stone plaques upon each house in town, a personalized touch that helps make the structure a home.

“My role at Alys has really changed and grown throughout the years,” David says. It was clear from the beginning that his work is impeccable, and his relationship with the Alys Beach team has deepened as his body of work has extended into a broad range of projects. While he still creates signage for the buildings at Alys Beach, he’s now working on interior and courtyard metal details, from handrails to custom water spouts, to inlays for floors.

“I specialize in doing what I haven’t done before,” he says. He’s a fabricator by trade, but he’s a classically trained artist at his core, motivated to do good work and inspired by his travels and artists from around the world who’ve honed their skills in different environments.

“My wife and I love to travel. I was born in Africa, and every four years or so we came back to the states to visit the churches that supported our family’s mission work. Traveling is in my blood. I live to do it. And I try to see art wherever I am,” David explains.

“There are many artists and architects who have come before me, and inspiration is everywhere. Every few years Geri and I visit Venice to see La Biennale di Venezia in Venice, a contemporary art show featuring artists from around the world. We both love being inspired through immersion. But, inspiration comes from everywhere. It comes from art and nature, and inspiration comes from your whole life.”

That’s been the trajectory for David and his career, holding fast to his roots and the routes he’s traced across the globe. His life a great circle, like a meridian, encompassing a world that contains multitudes.

When David’s not working, he’s … working.

Well, at least in the sense that he’s continually looking for new ways to perfect a craft or find a solution to a problem. He was born with that drive, and it was nurtured over time by his parents, his training, and an innate sense of curiosity.

“Hobbies? I like to cook,” David says. “Well, I like to eat, and so, I like to cook. My parents cooked. They were great at it, and I learned from them.”

Another passion instilled in him by his parents, another call back to his time in Zimbabwe: his parents believed food should be nutritious and should taste good. They encouraged that balance of good health and good flavor.

“I cook Southern food, but not in the traditional way. My mother was from Kentucky, my father from Virginia, but those formative years of my early life were in Africa.”

David continues, “I remember that my father made chocolate meringue pie, and it was very good. And my mother made lemon meringue pie, and it was fantastic. They made lots of things, but as a child, of course, you hold onto those desserts, of course.”

David has certainly held on to those desserts and the memories they hold for him. Perhaps these dishes and his desire to hold their tradition are part of his inspiration and his motivation to perfect his craft. And he’s fairly certain he’s just about perfected each recipe, having made having made hundreds of lemon and chocolate pies over time.

“Would I ever open a pie shop? Of course not. Then it would become a job, and I don’t want a job,” he laughs.

“I like working; I should probably retire, but then I’d have to figure out something to make. And that’s what I’m doing anyway. So as long as I’m making new things, it doesn’t seem like work so much. It’s interesting, keeping my mind going. Why should I ever quit doing that?”