There is beauty in that which is limitless. In a space without bounds, ever expanding and simultaneously ever shrinking, that which may seem static is only true for a moment. As we stand on the shore gazing to the Gulf’s steady horizon, the only thing constant is the presence of change—of waves pitching and undulating. The beauty of that vastness of possibility engages our curiosity and causes us as humans to take a closer look at our world and at our grip on it, approaching it with fresh engagement each day. New media artist Ian Gouldstone challenges us to see that.

Gouldstone, digital and projection artist and featured artist at Digital Graffiti 2019, is particularly interested in the infinite and the possibilities therein. Born in the UK and having spent his adolescence just outside New York, Ian has always engaged in the study of how subjects change over time in environment. His work, Wanton Boys, which was featured in the 2019 Digital Graffiti festival was an exploration made manifest upon the bridge at Lake Marilyn.

Ian began his career as an artist by way of the study of mathematics at Harvard. He says he found calculus beautiful. In fact, to hear his eloquent—nearly poetic—exposition of theoretical math, change, and human curiosity is to witness a man in awe of beauty in its most essential form.

“The basis of my art is the exploration of the infinitely large and the infinitely small and the possibilities within structures in that space,” Ian says as he speaks of his Harvard undergraduate math education. From Harvard, he researched and studied animation at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, working with the Gesture and Narrative Language group to study the rich contradictory and often ambiguous relationship between visual, technological, and physical communication. His colleagues there confounded the stereotypes of a scientist, with backgrounds ranging through all spectrum of society and study, and one among them, his mentor and professor Jestine Cassell, encouraged him to take his animation study even further.

“You can go to art school, Ian,” said Cassell. “You’re allowed!”

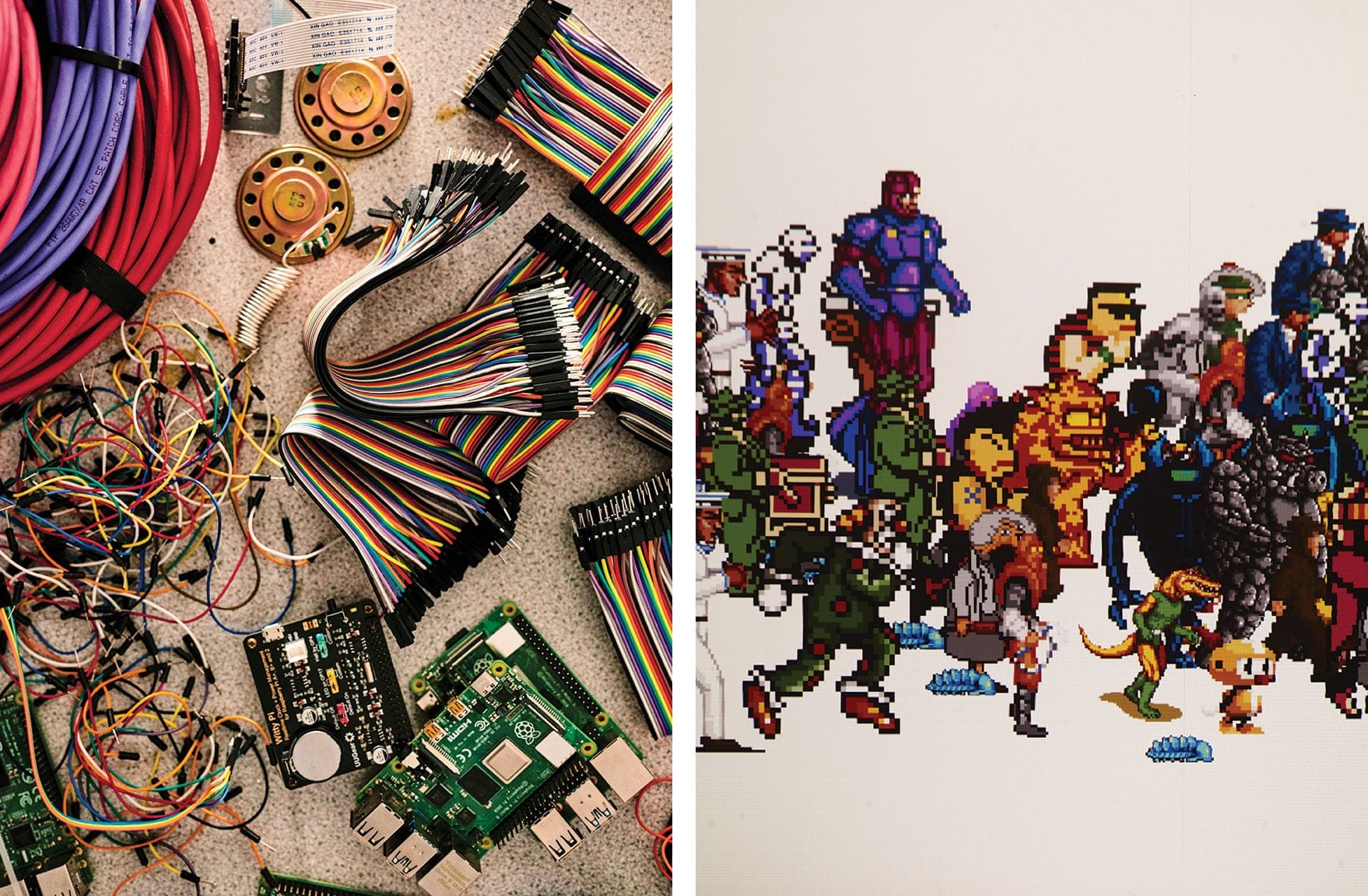

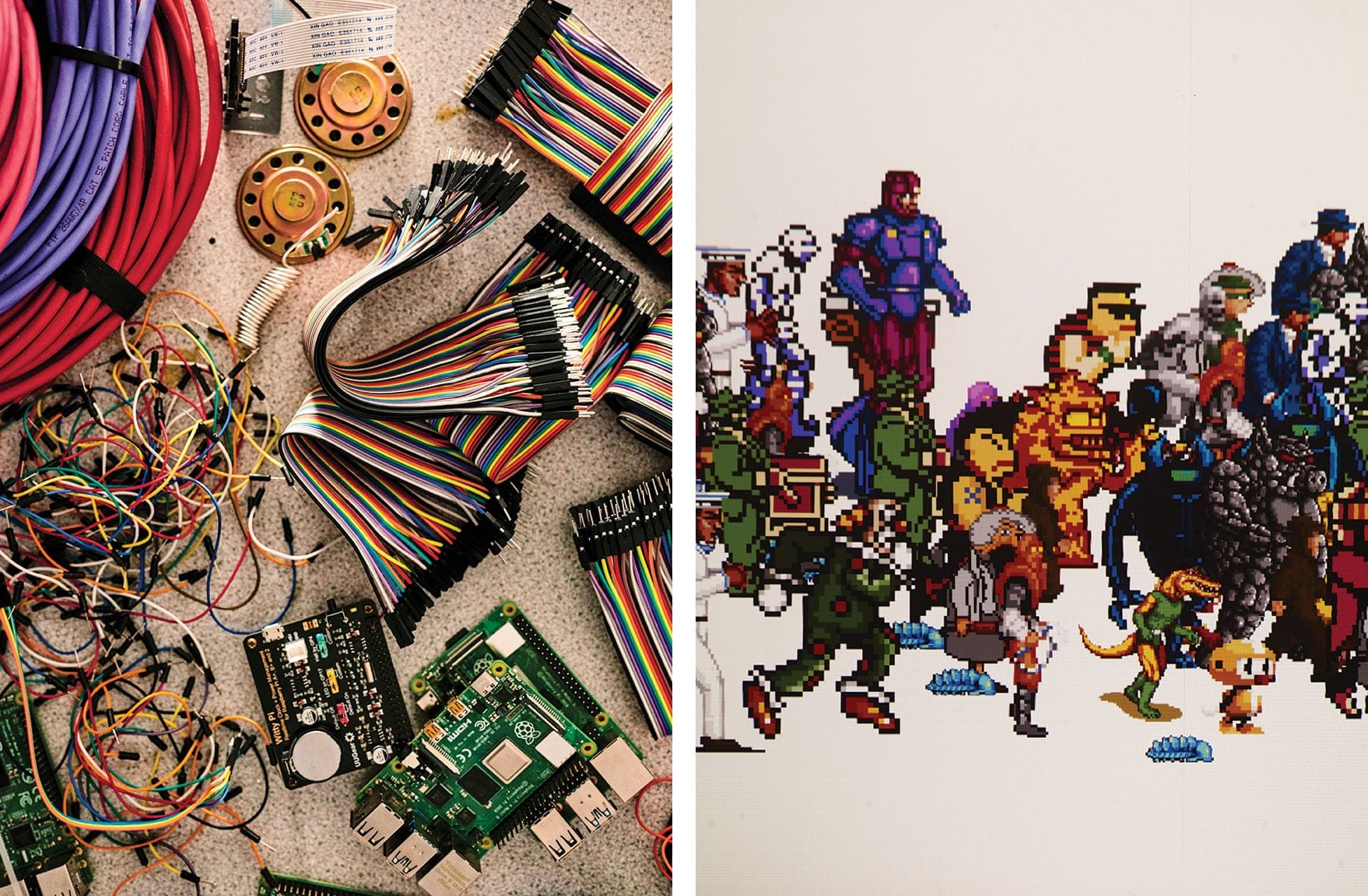

And he did. He went on the Royal College of Art in London. He studied multiple mediums and delved deeper into animation. He moved to Australia to apply his knowledge in the entrepreneurship of his indie video game company. He studied the traditions of fine art. In all these paths Ian has journeyed and still walks upon, he has done so seeing great possibility in each. Now Ian is living and working back in London, creating dynamic pieces of art influenced by his own participation in art of many forms. He hopes he will challenge his audiences to work a little harder when they view art in the world.

“I create these 'possibility spaces,’” says Gouldstone. “And using technology, I can write a set of rules through code within infinitely large spaces, and to the computer I say, 'let’s explore this space over time.’”

“Through the process of navigating this space, the system sort of anthropomorphizes. I never really know what’s going to happen. It’s a multidimensional space with all these parameters, and it teleports around with different velocities. When people, viewers, start to see things in my art, personality maybe, that’s never intended, but it is really rewarding because it means they are looking closely.”

And when viewing Ian’s art, or arguably any piece of art, we as the audience bring our own changing relationships and narratives from our cadres. We break down these infinitely large spaces with our own constructs, and suddenly, infinity is not so intimidatingly large.

When Ian arrived at Alys Beach for Digital Graffiti, he applied his instincts to the environment at Lake Marilyn.

“Part of the process is not just imposing the work on a space, but rather, it’s about trying to find a symbiotic relationship between the two. I try to use my work to highlight some of the more interesting features of the architecture,” says Gouldstone.

“There are so many often overlooked details that are fantastic, and I want to reward people for taking the time to look and to notice.” He references the tower on the bridge, and how if you looked up within the beams you’d witness the inhabitation of his colorful crosses in that unexpected and often unnoticed location.

Ian uses his art as an avenue to incite and encourage human curiosity. Through his work, he builds a narrative framework, a place for abstraction within a scaffolded system, and it's in that space that imagination can take hold.

“I think it is wonderful to be curious about what you’re looking at,” he says.

“Looking itself is the embodiment of curiosity, and curious is one of the best things we can be. As we're actively looking at the world. That's when we're most alive.”

Throughout human history art has been a mode of social and political commentary, and Ian admits that sometimes he questions if his art (he gives a self-deprecating laugh as he calls his work “digital doodles”) should do or say more. But he always goes back to his original intent, the reason he found calculus so beautiful, the reason infinity stands not as something to be intimidated by, but rather, as something to be inspired by.

“Collectively, as artists, our job should be to empower people to ask harder questions of the world and to be more curious of it,” he says.

“I always go back to the idea that art is about looking, both in creation and reception. It is about inviting viewers to be thoughtful, to dig deeper. By strengthening imaginations and encouraging curiosity. And my art does that, I hope.”