The Metal Man

“How much do you want for The Dragon?”

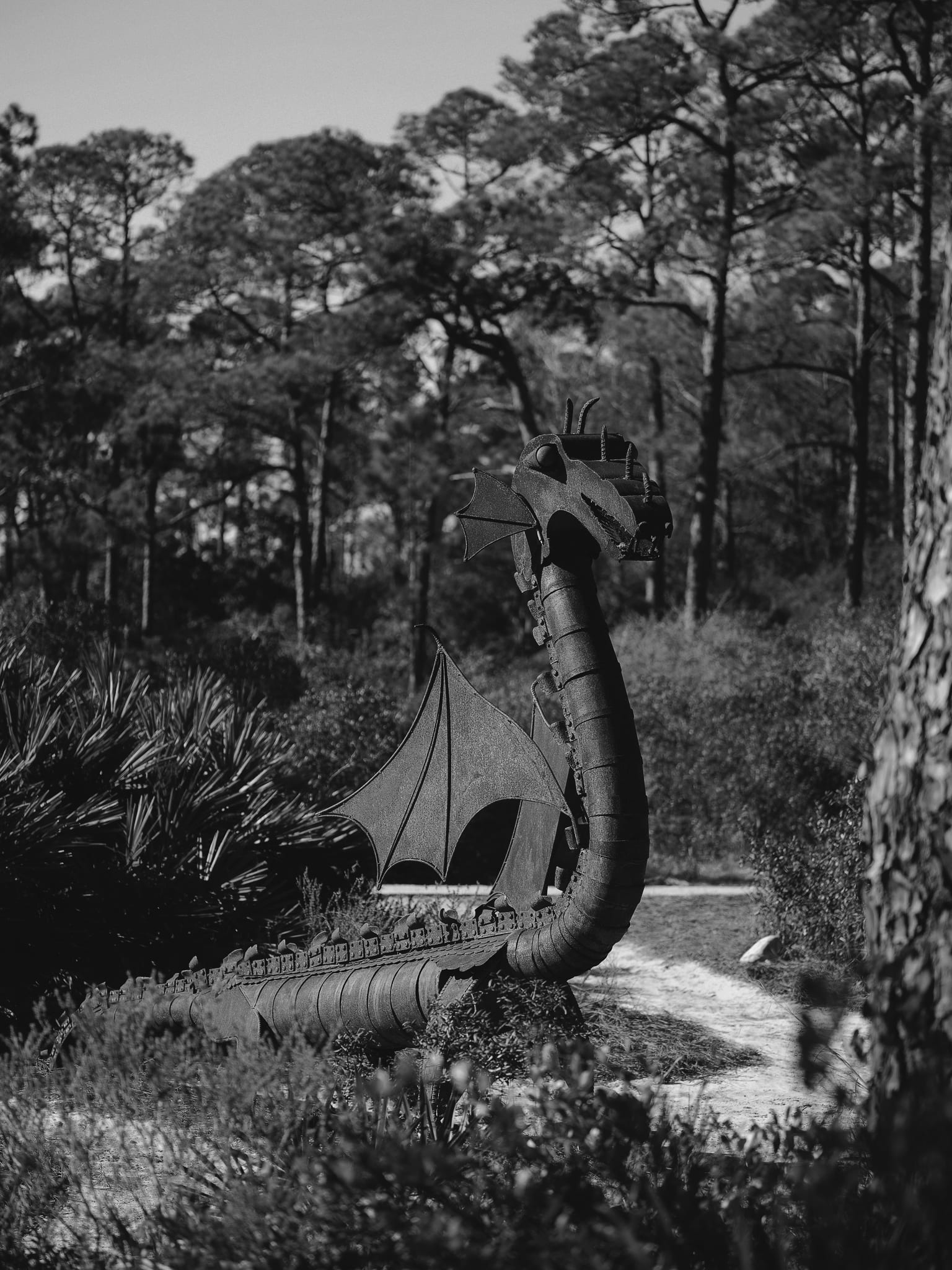

It was not the question Charles Lawson expected to hear from the nine-year-old boy standing in front of him at Rosemary Beach’s Flutterby Art Festival. The boy’s curiosity was assuaged by an attentive father who came to investigate the metal creature that had so captivated his son. As luck would have it, the boy’s father, Jason Comer, was the president of Alys Beach. A few short months after this chance encounter, The Dragon was transported to its home along Alys Beach’s Nature Trail. It’s as imposing now as it was on that day fifteen years ago. A fearsome, fanciful, rusty beast guarding the swamp from which it seemingly emerged. This story, just like great art, becomes even more interesting—more endearing—when the viewer gets a glimpse of the maker behind the piece. In this case, the architect of the dragon.

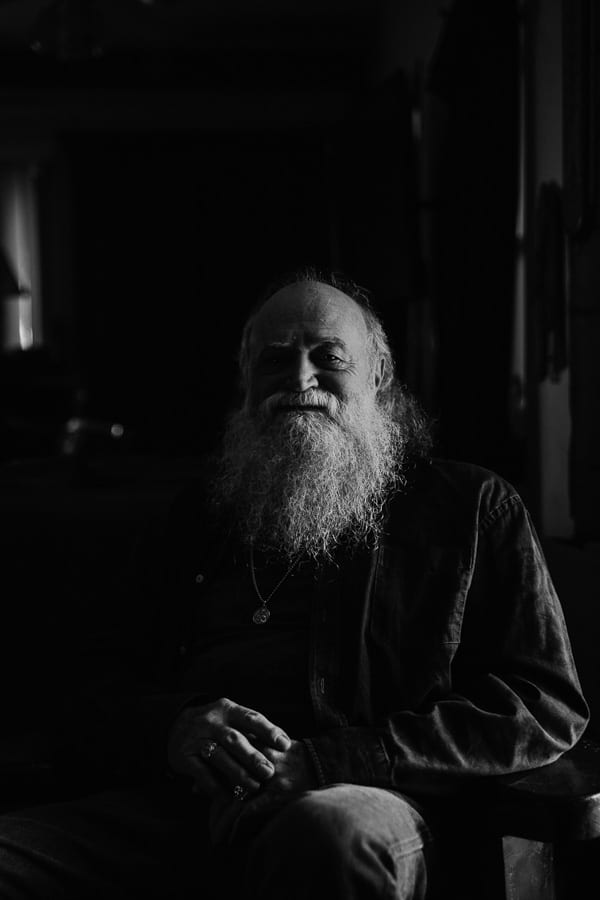

Charles Lawson, a house painter-turned-metal worker-turned-artist, is what many would describe as a colorful figure. With a beard white and wild and full personality, Charles upon first impression, one can tell, is a man of many stories and great creativity. Even his home defies definition in an age where it is difficult to go “off the beaten path." Nestled in rural Freeport, Florida, Charles and his wife have made their home upon property that has been in the family for generations. The large, wooded swath of land is concealed, undiscovered—you won’t find it on Google Maps, and newcomers and visitors need resort to the old tactics of landmark navigation to make their way to Charles’ home. But within its bounds Charles finds inspiration to create. It’s an artist’s oasis of sorts. His house itself is an ongoing piece of art, replete with custom additions and collections of curiosities, and scattered throughout the property are artifacts of artistic endeavors. But it’s just out back, in an open-air studio, that Charles brings vision to life through a metallic medium.

Lawson is warm, generous, and an easy conversationalist. As casually as he discusses the weather or recalls a childhood tale is as casually as he discusses his career. A career that is prodigious and spectacular. And while many not see potential in the materials scattered across his workbenches, he proudly maintains that there is no such thing as scrap metal in his studio. Only metal he hasn’t used yet.

Charles also doesn’t consider himself an expert and says artistry wasn’t the original plan. As he shares his story on a Sunday evening, his daily cranberry cocktail in hand, he explains that he simply found something he enjoyed and kept doing it. An interesting assertion when only a glimpse of the cattails structure in his home screams of wild and immense talent. As he speaks, his voice is grounded, just as his demeanor, emanating a certain warmth.

Lawson began his connection with 30A when he painted the first homes at Seaside over thirty years ago. As his family grew, he sought a more profitable trade and was introduced to metal working by an old friend. He began as a wholesaler, buying pieces with the idea of reselling them to local builders. Many of the pieces came in bowed or concave. Knowing he could improve on what he saw, he purchased a welder and taught himself to use it. Other lessons learned over the course of life were suddenly useful. Cranking the forge in his grandfather’s blacksmith shop. Time spent working at a foundry as a young man in Arkansas. New lessons were also learned. Metal hits back. Rust is your friend. Expect cuts, burns, and bruises.

Lawson’s work can now be found all over Walton County. The railings of the first houses at Alys Beach, railings and shutters at Gulf Place, a solid bronze exterior in The Retreat, and the fountain at the Coastal Beach Library, to mention just a few. Even Alys Beach’s flagpole can be counted among his numerous works: A builder of ship masts in Panama City constructed the pole while Lawson designed and built the base. For hurricane strength winds, no less.

Word of mouth has always been all that was needed to keep Lawson busy. On one particular project, the architect specified in the renderings that Italian steel be used for a stair rail. This level of detail was unusual, and afterward, Lawson found he had developed a taste for only Italian steel. It is more user-friendly than other metals, so he intentionally forged a good relationship with the single supplier of Italian steel to the U.S. Years later, a vacation to Italy with his wife proved to be both educational and affirming of his calling. He found the work of his Italian counterparts to be unusual compared to what he saw at home. He paid attention to details most people wouldn’t, things like shutter hardware. He photographed and touched as much as he could. The brain is most certainly a sponge for the things that interest a person, and Lawson’s interest began to grow in ways he could not have anticipated.

His adopted work philosophy is the opposite of that of a sculptor. The work of a sculptor or carver means cutting away anything that does not contribute to one’s vision. Lawson, conversely, adds metal until his work has the desired effect. Over the years, aptitude became proficiency, which became mastery, which became artistry. He found himself collecting and working with metal at home simply out of pleasure. Selecting bronze, steel, and iron (never aluminum!), his noncommissioned creations grew literally and figuratively. His 18-foot trailer (he hauls over one ton of metal at any given time) began making appearances not just at construction sites, but also at local art shows. His first, the 1992 ArtsQuest Fine Art Festival, was impressive, as all artists were juried into the show. The Dragon was built for one such show, and Lawson won the “best of” category another year for metalworking.

Working more intimately with metal, there were still things to be learned. For example, it is possible to suspend art by sealing it. But Lawson does not seal his metal work with paint. Instead, he allows the metal to rust and then seals it at a certain point so that the patina is captured forever. The final effect after a clear coat is not unlike stained leather. Only the most curious and determined of minds could have begun as a painter and, years later, developed an entirely new way of “painting” metal. These techniques have been used twice on The Dragon—once during its creation and again during its restoration in 2020.

Now in his early 70s, Lawson is approaching a new milestone in his career—his artistic pursuits will soon outnumber his commercial projects. Not a day goes by that he doesn’t think of something to sketch or build. His studio will remain a hub of activity. And then there is the possibility of additional sculptures for Alys Beach as it expands—a thought Lawson relishes. He anticipates music and art to fill much of his time in the years ahead, and we can only hope those gifts are shared with the residents and guests of Alys.

As children, we are told stories with mythical creatures often end with everyone living happily ever after. Let us hope that our Dragon and its creator are no different, as they both epitomize the art and beauty that is Alys Beach.