At Alys Beach we celebrate art in all its forms. Whether created in nature or by the hands of skilled artisans, art enlivens our community and connects to a sense of place. In this edition of the Artists of Alys Beach, we spend time in Somerset, Kentucky, with Dan Dutton, the sculptor who created the bronze turtles along Turtle Bale Spring.

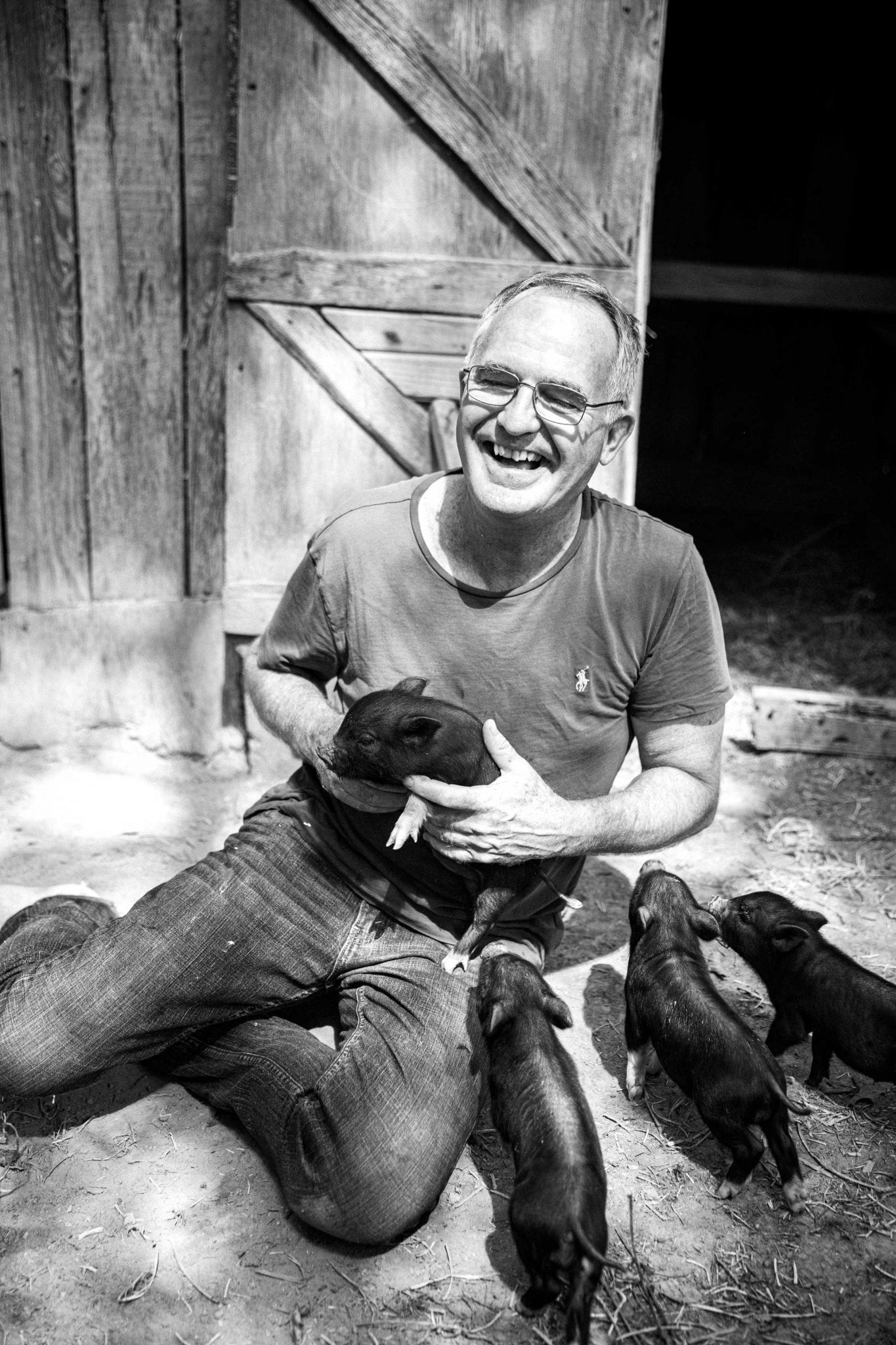

As a young boy, Dan Dutton sat in his back yard, beating flat a muffin tin with a hammer. It was his first piece of art, he recalls explaining matter-of-factly to his mother who watched from the kitchen door on his family’s 200-year-old farm in Somerset, Kentucky. With his hammering he kept sharp tempo alongside a secret droning melody held within the Appalachian Mountains; the beat moving with the echoes of his ancestors through the trees and over the hills. In that moment of creative endeavor it became clear that in his five or six short years, he had already become a part of something greater than himself. There’s a music—a narrative, perhaps—native to Appalachia. An art that is innately tuned within Dan that has shaped how he sees the world, whether that world is southern Appalachia, in tea garden in Japan, or along the pedestrian paths of Alys Beach. He is an artist in every sense of his being, excelling across multiple media as a self-taught composer, painter, sculptor, and designer. His ability to find depth and meaning, even a bit of whimsy, in the world around him is inspiring.

“Both of my parents were farmers,” says Dan. “They were devoted to the land, but, and maybe because of this, they appreciated beauty and art.”

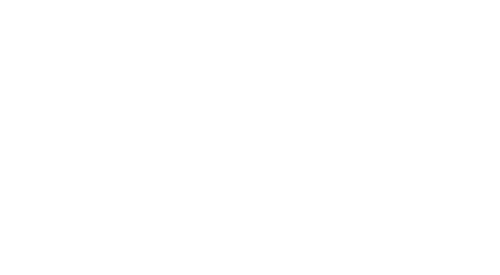

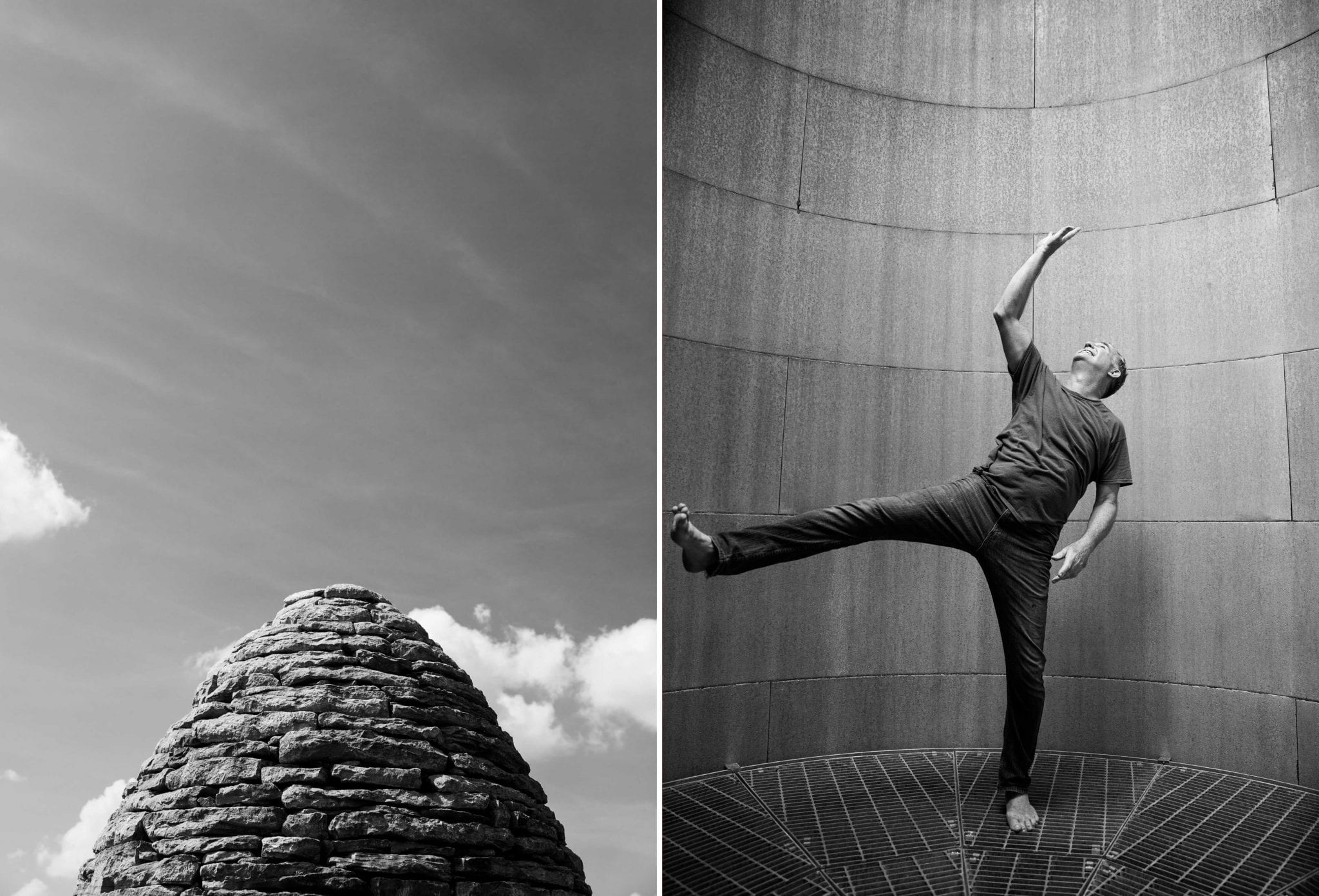

“Both of my parents were farmers,” says Dan. “They were devoted to the land, but, and maybe because of this, they appreciated beauty and art.” That appreciation has developed into an utter passion for Dan, one that knows no bounds. It seems to give him a sense of duty, fresh each day when he wakes and swings wide the door to his old family home, to seek beauty that lies within everything around him, and from that to create. For Dan, to step outside (often barefoot) and walk to his pig pen to feed the piglets is an opportunity in and of itself to bring meaning to life and art into what would otherwise be a mundane task of life. To view the world with such whimsy and wisdom is not something simply attained, but rather, built into a person from his beginning, and perhaps even before that.

“In the Appalachian Mountains, and especially in Kentucky, there is a history of long story-songs that originate back in the 1600s in Scotland and Ireland. ‘Murder ballads,' as they were called,” explains Dan. “As a child, I remember my parents and older people in my community singing these songs. I can remember closing my eyes and listening to them, and I’d see the story like a film. I was seeing it as a visual, imagined and embodied thing, and that was the reason I was driven toward recreating that internal experience in the real world.”

Dan, who had no formal art training, soon moved from muffin tin art-making to further extensions of his creativity. He began selling paintings when he was just fourteen years old. By the time he was seventeen, he had built his first studio and was making a living doing what he loved on his own terms. For some, the success attained in both sculpture and painting may have been enough. But his unique perspective on the world allowed him to pursue another avenue of expression. At the age of 29, Dan composed and produced the first of nine operas.

Theater director. Opera composer. Ceramist. Artist in Residence. Set Designer. Sculptor. Painter. Costume Designer. None of these things are at all disparate to Dan. These tactile and sculptural experiences are simply the expressions of a mind keenly aware that art can and does reside everywhere. That every detail carries within it deep meaning and inherent beauty.

These tactile and sculptural experiences are simply the expressions of a mind keenly aware that art can and does reside everywhere. That every detail carries within it deep meaning and inherent beauty.

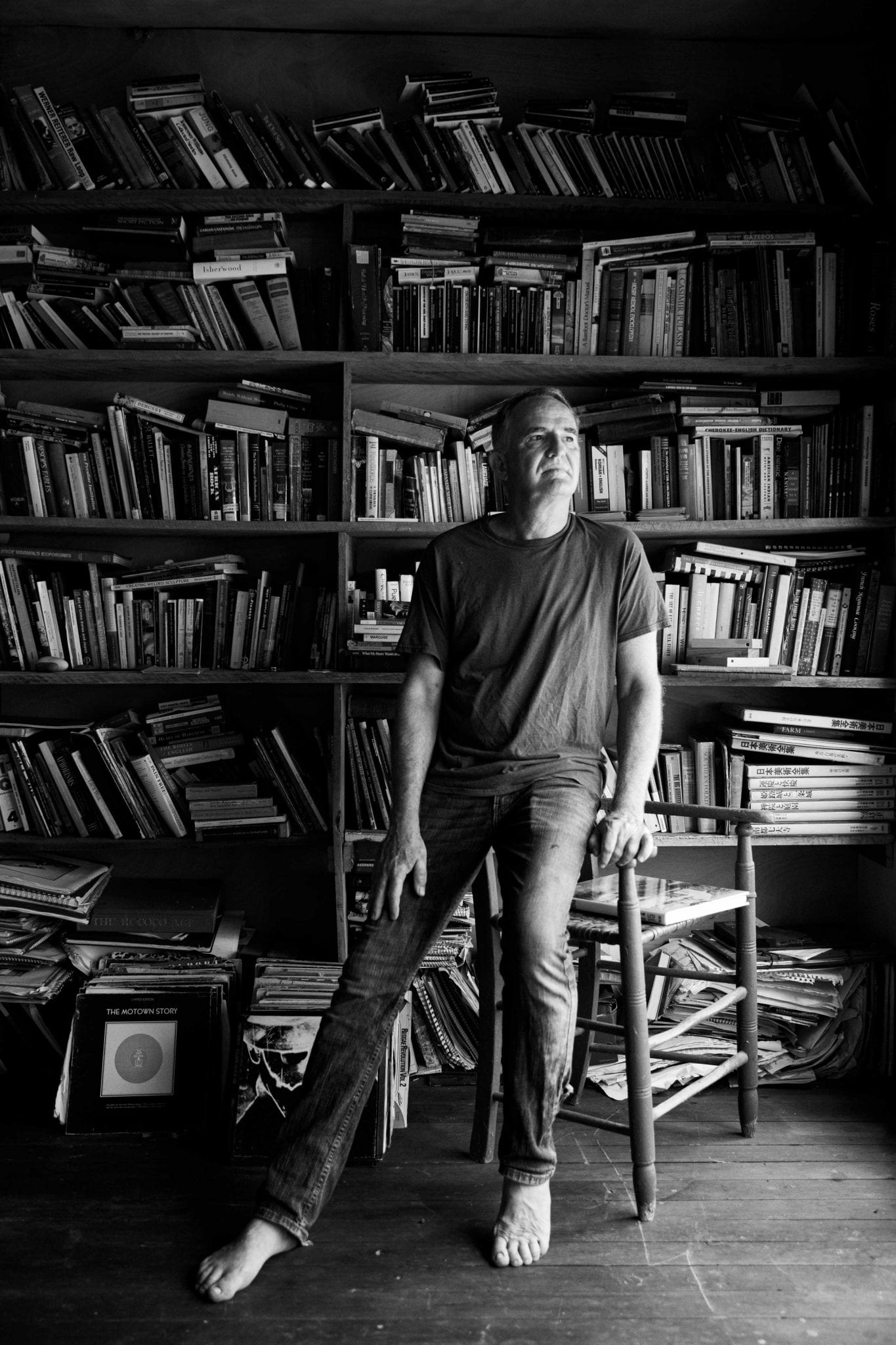

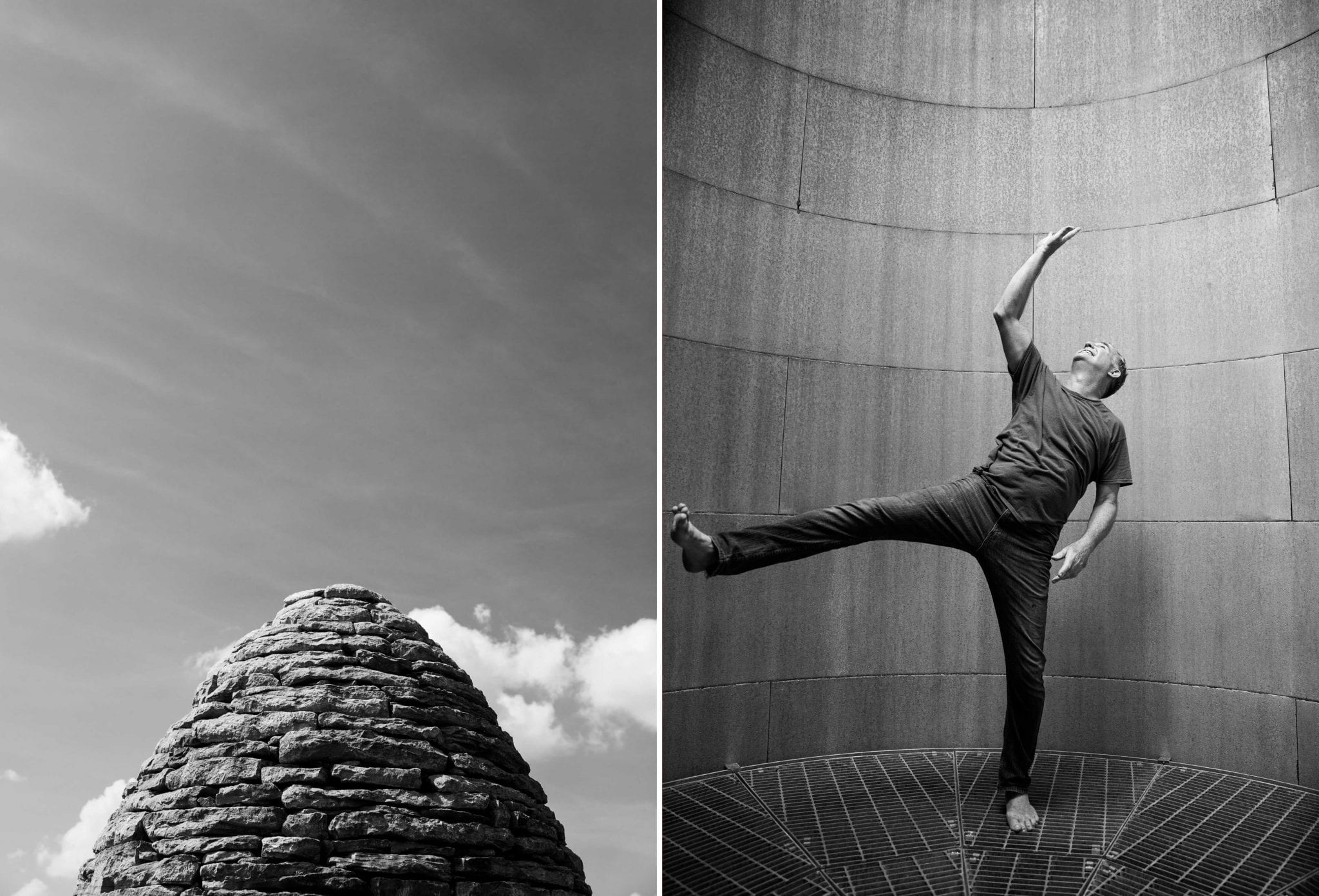

So as Dan walks his property, walked by his ancestors before him and laden with storied voices, the world around him is truly a canvas. His own touch is sprinkled throughout the grounds: moss gardens inspired by his twelve years in Japan studying the sacred tea ceremony, stacked-rock statues, and metalwork sculptures all built here in his creative oasis of acreage. Dan has both a painting studio and a sculpture studio on his property, and he is building a new studio whose grand proportions will rival his own artistic vision. In a 40 by 80 foot building with 16-foot ceilings, Dan and his sculpting partner, Jesse Rivera, will take their work to new heights.

“I lived in Chicago for a season where I worked as artist in residence for Rookwood Pottery, creating a line of ceramics as they prepared to bring their work back to the market,” says Dan.

It’s during his time in Chicago that Dan met Jesse, a metal worker and highly skilled welder. The unlikely duo has decades separating their ages, hundreds of miles between their hometowns, and each has a history that connects them to the craft in an entirely different way. But their mutual appreciation for art and their nearly-eccentric insistence on perfecting the details led them to imagine what they could create together. Jesse left an urban life in Chicago and now works with Dan in a 200-year-old carriage-house-turned-painting-studio. They are creating a stunning collection of metal sculpture, some of which has found its way 650 miles from Somerset, Kentucky, to Turtle Bale pedestrian path, just a few blocks over from Somerset Street in Alys Beach.

“When Ben Page of Page|Duke asked me to do this project, he could have hardly known how much affection for turtles I held as a child,” laughs Dan, as he reminisces about how he studied them throughout the years, the way they moved, and the details of their being. “Since boyhood, growing up in rural Kentucky, I have always been an amateur aficionado of animals. I studied the natural sciences nearly as closely as I do the arts. The two are inherently connected, and all created, visual imagery ultimately springs from the natural world.”

"I studied the natural sciences nearly as closely as I do the arts. The two are inherently connected, and all created, visual imagery ultimately springs from the natural world.”

At one point in the design process, Ben asked Dan if he could, perhaps, make the turtles a bit more…whimsical. Dan laughs as he reflects on that request: “I am the king of whimsy!”

That joyful perspective is one that has grown a prolific career in the arts from a small, storied corner of Kentucky. Dan’s view of the world is grown out of a history of interacting with the natural environment and exploring the beauty and delight that is found within the ordinary. It seems quite fitting that whimsy rises from that rich foundation of history, that Dan can look at anything and everything around him and smile and say, “this, too, is art.”