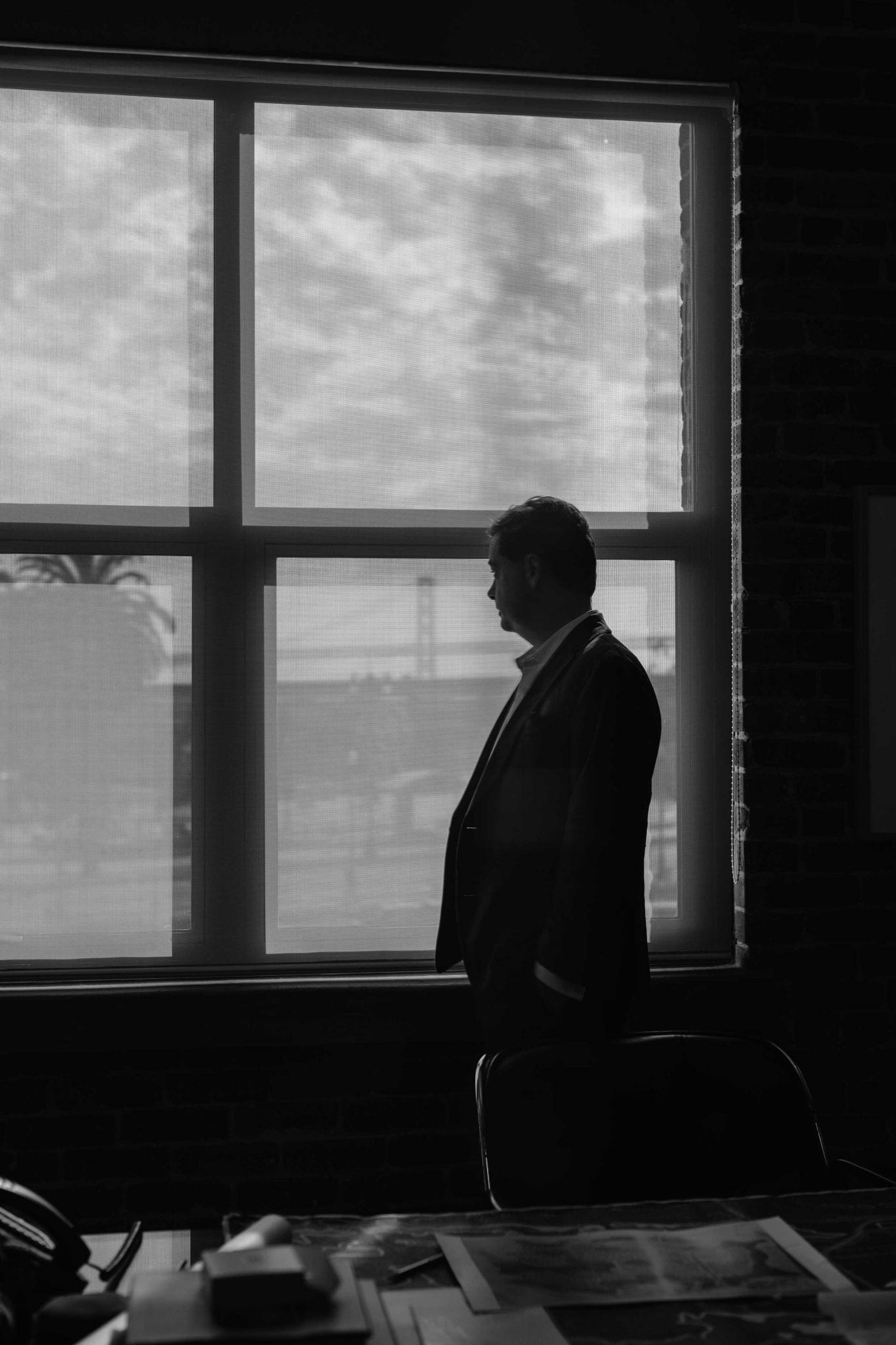

The structures of Alys Beach are a representation of our community. Within each home is held memories of time spent with family and friends. Written into the plans of each public space are the stories told as a community gathers together. The architects of Alys Beach, in a way, help author these stories. As we continue our series of the Architects of Alys Beach, we spent time with Tim Slattery, partner at Hart Howerton and lead architect of the Beach Club.

Drawing, for Tim Slattery, is the purest form of communication. As a child he asked for a thousand pencils for Christmas, and he designs still today by hand, during the week in his office and on Saturdays in a study in his home, the soundtrack of his daughters’ voices coming from the backyard. He hopes for his designs to communicate a sense of home for everyone who walks through them, an expanded sense of personal space— a feeling of comfort, retreat. His other aim: experience— the experience of light, the experience of the landscape, the experience of subtle surprise and architectural elements that delight. His benchmark for a successful design is not critical praise, but a space in which he sees people relaxed, children laughing. Tim too thinks about the people who work behind the scenes to make the experience special. A source of inspiration for him? Walking through the underbellies of buildings— popping up in kitchens, taking service elevators. He wants to know how the space is being used, making it easy for everyone using it, pleasurable even.

In conversation, as you might imagine, Tim is exceptionally easy to talk to and indeed kind. He is one of those who always knew he’d be an architect and he has a steady confidence that his clients must find reassuring. He is shy to take any credit for himself, and will immediately pivot into praising the other designers he works with at the design firm Hart Howerton where he is a partner. He seems to derive the most satisfaction from designing buildings that are both beautiful and useful, that complement their surroundings, and from the experience of making other people happy.

Cassie: Tell us about your childhood. Where did you grow up? Tim: The simplest answer is that I grew up in upstate New York, in Rochester, but for my dad’s work we traveled a lot and moved to different places. I lived in Madrid for three years when I was a young child. We moved to Melbourne, Florida for three years. Then I went to school in the Midwest at Notre Dame and part of that program was living in Rome. So, I traveled all over and through that have kind of learned to love all different kinds of places. I haven’t stayed in one place. I lived and worked in New York for almost ten years and now I’ve been in San Francisco for twenty. But I continue to do work all over the place. So I guess I’m a little bit of a nomad in the sense that I grew up traveling and, even now, while my home base is in SF, I travel a lot for work, all over the place. One of the things I really appreciate about traveling is seeing all of these different places— not only architecture, but just the way cultures are, and fashion, and how people operate. It’s really interesting.

C: Yes, it’s a gift. How did you spend your time growing up? Did you have something that remained the same even in all of the different places? T: I always drew, sketched. My mom always joked that one year when I was little I asked for a thousand pencils for Christmas. I just loved to draw and I continue to love to draw. Part of that is just being a kid. Even when they can’t speak very much, kids draw to describe. As they learn to speak, and now learn to communicate on their iPhones, they pull away from drawing as a form of communication. But I think drawing is the purest form of communication because it’s just you and it’s the best way to describe. I think that a lot of architects play with all sorts of models and Legos and things like that when they’re little. I’ve always loved to create things.

C: Did you identify as an artist, as a drawer, when you were little, or was it just something you did? Did it feel like a calling, like you had a future in it or did you just go with it? T: I think I probably was one of those people who knew I was an architect at four. I didn’t know what an architect was, but my dad said I should probably be an architect. He’s an accountant and he wanted to be an architect. I joke with him and say that it was too hard for him, but he said, “Well, maybe you should be an architect,” and I said, “What’s that?” and he said, “Well, you get to design and build buildings,” and I said, “Oh that sounds pretty good.” So, when I applied to schools I was already pretty clear from day one on what I wanted to do.

C: They still teach drawing by hand at Notre Dame, correct? T: Yes, it’s a core piece of the curriculum, both drafting and painting and now furniture making is also a big piece of it. And also the study of history is really important. You may spend a year in Rome. So it’s not like you’re looking at books alone. You’re also going to these places and sketching and walking around so it’s pretty magical. I remember coming back from my year in Rome and looking around and laughing thinking, wow America really needs some help. And also noting how young we are, relatively speaking.

C: We have people like you for that now. So you still draw today then? T: Yes. It’s a bit of a lost art I think. It’s a core piece of how we design and work. We employ technology but it’s always kind of rooted in hand thinking.

C: Do you still draw for fun? T: I do. It’s rare that I don’t have a pen in my hand. I have two daughters and my wife is an architect as well. My daughters are always joking that I’m always drawing something. I was always interested in Disney and animation. For awhile I thought I wanted to do that. But someday I have a dream of doing a children’s book with my daughter. I think if I was not an architect, I’d be writing stories— or rather illustrating a book and having someone else write.

C: That would be so wonderful if you could do that with your daughter one day. I hope you will. T: It would be awesome.

C: Do you see a way that your past influences your work now, as far as travel goes? Is there any kind of through line from that to where you are now, beyond the drawing? T: I think I have a pretty healthy respect for working in a place like Alys Beach because of my travels. I’ve seen a lot of stuff all over the world and you look at Alys and understand that it is a very unique, special place. Like what I saw in my time in Europe, it’s built to last for time. Not all the places we work in America are. They’re doing something quite meaningful down there and so we’re doing our best to operate in that arena, to complement things. Our founder Bob Hart always has this line— “Tread lightly on the land.” We’re always trying to be very respectful of the places we work.

C: What gives good design longevity? Does that feed off of what you were saying? How do you give something staying power? T: What we have done as a practice is design complete environments, which includes the whole landscape, site, context, interiors. There are no lines between anything and I think the Beach Club represents that. That design usually lasts because it’s rooted in natural features, certain climate, certain vernaculars, local trades and materials. So understanding those conditions is how a project becomes ageless. When you get the kind of spaceship landing on a flat piece of land and it’s an architectural statement, I think that ends up looking fashionable and out of date just as it’s getting completed.

C: What does it mean to you to design a home? I know you work a lot on bigger projects— communities and resorts— but what about a home? T: It’s all scalable. So, we do a lot of clubs and hotels and all sorts of other stuff. But at the end of the day, the home is a place where people feel comfortable. It’s a retreat and it’s a certain scale of room size. I think people just like to spend time together and just be in an environment that makes them happy. Designing a home, I feel like we’re always trying to design something that feels comfortable and familiar. Home is a very personal thing.

C: What does home mean within a community? Perhaps it’s just an expanded version of your individual space? T: In communities that have a point of view, and it’s followed through all the way, there is a clear sense of space because there’s a strong language of architecture and landscape and all of that. Obviously Alys Beach is exactly that. It’s one of the purest points of view that I know. It’s quite uniform. People bought in Alys in large part for the design of the community so you’re trying to plug into that and complement it and not try to be different.

C: Not brand new… T: Exactly.

C: How does what already exists in a place influence the way you design a new element of a community? In designing the Beach Club, you focused on what’s already there— the particular point of view, the homes, the landscape, the… T: With the way the town was set up, there’s a clear understanding of what they call the Amenity Triangle with Caliza, Zuma and now the Beach Club and what we’re trying to do is understand the context of the overall place and then try to understand what Caliza did, what Zuma did, and how the Beach Club would be complementary to those facilities without trying to copy them. This will be the gateway to the beach. Currently there are the dune walkovers to the beach but this is going to be a major game changer for how people live and get to the beach. We really wanted to tap into that dynamic. The beaches in 30A and the Emerald Coast are some of the most beautiful I’ve ever seen. So we’re just trying to complement that scene. In a way we are describing the character of the Beach Club as it’s almost like the beach washed ashore into the Club. Metaphorically there’s this notion of the casualness of the beach— barefoot, sand, running around— and we wanted that feeling to come up into the Beach Club and by extension into the Beach Club Plaza. It’s a place that we think is going to live different times of the day. It’s going to be a morning spot, a daytime spot, an evening spot. In an interesting way, there aren’t many places along that corridor that have great views of the sunset which is magical. So, part of the idea was by building the building perpendicular to the shore versus parallel, you’d have views up and down the shoreline and not just straight on, which is far more dynamic we think. We are trying to do many things with the building but in a very simple way. Just like many places, the architecture evolves over time. We looked at the roots of what Alys Beach’s architecture was based off of. I think at least one influence was St. George’s in Bermuda which has very simple, very classic forms. We tried to go back to simpler forms, less ornate moves— a very pure simple building.

C: Can you speak more about your feelings about Alys Beach and what it was like to design for this place? T: I was just there with my family so I love it enough that I want to go vacation there all the time. It’s such an inspiration to work in a place like Alys. Everywhere you look is beautiful. The places that I like to go on vacation are beautiful places where I can walk around and see beautiful architecture. You don’t have to go to Europe to do that only. Alys Beach is one of those places. There’s a handful of places that I can think of that have that level of beauty in architecture with that level of natural beauty with the beach. Usually you go to these beach towns and they’re pretty dodgy. This is this kind of purity of architecture and purity of beach. It’s an inspiration. The talent of the people that are working there is pretty stunning. We feel humbled but excited to be participating in that.

C: Do you have a favorite project? One that’s stuck with you? T: I would say one of the favorite projects I’ve ever worked on is Palmetto Bluff in South Carolina. I worked on that project for about ten years. Both the Master Plan and we designed buildings there. It’s one of those places that has a unique and consistent point of view over a pretty large piece of land. To be able to have some impact on twenty thousand acres— it’s vast. It’s pretty cool to be out on that river, on the water, and look back. I also really enjoyed working on WaterColor. That was in its early days. I don’t think Alys had even started. Rosemary was underway but kind of bolting onto Seaside was an interesting dynamic. I was recently there and I think one thing that distinguishes WaterColor in an interesting way is that it has a very shady landscape and I think it feels very comfortable. There’s all sorts of distinct communities along the corridor. It’s had time for the landscape to grow in. Alys Beach is still growing in. The older areas feel like that and I think it’s just going to get better over time.

C: Your wife is also an architect. What kind of home do you have? Is it something you designed? T: Hardly (laughs). We live in SF in a 1911 Edwardian flat. We’re right next to Golden Gate Park. We did recently redo our back garden and that has been pretty amazing. That’s what we designed together, this big outdoor room. Living in SF means pretty tight quarters, but what I love about living in the city versus suburban is there’s a connection to activity all the time. We live half a black from Golden Gate Park which connects all the way to the ocean. And my office is right along the Embarcadero so you’re connected to water visually here. I always want to be near the water, I want to see the water. I think it’s very powerful. For most of Alys Beach, no one has a direct view of the water and I think the Beach Club is going to be the place where everyone wants to go to the water.

C: I grew up on a lake and I feel the same way. T:There you go. Part of being on the water has— it helps you from a wellbeing standpoint. Looking out over the water— light quality changes.

C: The water reflects off of my home so when the evening sun is going down, the shadows are just shimmering. T: That’s a good point about the architecture actually. Using the light quality of the Panhandle and the way the shade and shadow operate, you don’t even have to try too hard. The shadow creates a whole bunch of architecture by itself against the planes of the white. It’s pretty interesting. The whole community of Alys is like that.

C: Often the exploration of other creative outlets helps to grow and focus our creative gifts. How do you continue to grow yourself creatively? I know you said you still draw. Is there anything else you do? T: I would say travel. Not just to historical locations, but travel as part of work too. I get lucky, I get to travel to resort destinations in all these pretty magical places for work and to see what they have done is really interesting. Talking to a lot of bright minds in the hospitality industry and how they go about operating a hotel so that it seems very effortless for the customer while there’s a lot of hard work being done in the background. I’ll point out on the Beach Club that we take a lot of pride in understanding how operations works. We work really closely with the Alys Beach team to figure out how they’re going to run the building and serve the building and I think a lot about that whole piece of it. Not only seeing beautiful places, but also talking to the people who not only create it but who continue to operate it. We’re kind of students of that whole process.

C: And that feels like a creative jolt to you? T: Yes, I love going into, I’m not joking, into kitchens of hotels and other things. I was just in a project in Hawaii and I walked in through the back entry and came up the service elevator and popped up in the kitchen and I’m like hey, how’s it going, just trying to understand how you guys are doing things and they’re all just looking at me. At the end of the day, I think we’re designing for people that are enjoying it but also hardworking people and trying to make them enjoy it as well.

C: That’s admirable. It’s some meeting of beauty and function, right? For this to remain what it is, it has to function and be useful in some way. T: Exactly. Form follows function— always a good reliable quote.

C: What’s the most inspiring place you traveled? T: I was just in Italy and I would say Rome. The year I spent in Rome. I was just in a meeting where— I can’t specifically say what the forum for this was— but there was a survey that asked where people are happiest when they travel and number one was Italy and number two was Hawaii. And I completely got that because we were just in Italy and just in Hawaii. Italy has this weight of time to it, for me, and the idea of its early days is amazing. And Hawaii has this ancient feel also from an island perspective but it’s more natural. Then when you get to sections of Italy like the Amalfi Coast or Cinque Terra, it’s when you merge that crazy cliffside living with that natural environment. That’s pretty inspiring. The patina of age.

C: What helps inform, influence, and refine your understanding of the impact of design? T: I don’t know if this answers the question, but if I see people happy in that space. All ages. Whether you’re a young kid or an older retired person or somewhere in between. Where I am right now, the space in between, it’s if your kids are happy, you’re happy. That to me is the best. And I think it brings people together. Kids are actually the best critics of spaces. If they’re having a great time, it’s working. You watch the kids at Caliza and they’re using the space like you wouldn’t expect them to use it. That beautiful lap pool on the side that has this elegance— the kids are using it as their splash pad area. I think that’s what’s super magical about Alys Beach. As refined and beautiful as it is, it’s about the most family friendly place. You see kids all over the place. If the kids like the Beach Club, I think we’ll be successful.

C: How do you begin your day? Even through travels and work, do you have any type of daily ritual that starts you off in the morning? T: One thing I’ve been trying lately is not to look at my phone in the morning. I’ve been recently trying to go on walks through Golden Gate Park and do that to get ready for the day. I try really hard not to look at my phone until I get to work which is a huge change from what I used to do. Normally I like to draw before lunch and then schedule calls and all that after lunch. I need a clear mind to draw. If you’re getting bombarded by phone calls and emails it’s hard to sit and think. In an idealized version, I wake up, go on a long walk. We all pack in the car and I drop each daughter off at school, drop my wife off at work, get into work and then ideally I’m designing until lunch and then let the world come at me after lunch. This is just a funny story. There was a project I was working on in this seminary in northern California and it was this beautiful temple building and I was doing a drawing of it and my daughter was 3 or 4 and so I was lying on a couch on a Saturday, watching a Notre Dame football game, with my daughter on top of me, climbing all over me. My wife had gone out and she came back and I had been there for three hours and had done this etching, really beautiful drawing. At this point my kid had fallen asleep and I was still drawing. She was like, how did you do that? I was in my happiest place. I think the notion of designing when you’re relaxed versus gun to your head, get it done, is really amazing.

C: So you just try to make the space for it. T: Yes, try to make space.

C: What does a day of leisure look like for you? Where do you go? When you’re not working, where are you? T: I would say spend time with my family. Because I travel a lot, hopping on an airplane is not ideal. But where I am in SF, either driving down the coast or up to Napa is pretty amazing. One thing I really love about the whole Napa Valley is this fusion of wonderful architecture with wonderful natural scenery then you throw in that wine conversation, pair wine and food with landscape and architecture and it’s a pretty magical spot. It’s sunny up there and SF usually isn’t.

C: Do you listen to music when you design? T: I listen to all kinds of music and it depends on what time of the day it is. So it could be classical to classic rock. But some of it is to relax me and some of it is to wake me up. I have a small office in my house that opens up on to this garden that I mentioned. And I love to just open up the window and, again, my happiest is if my kids are playing around in the backyard and I’m not listening to music, just to them. That’s the best for me.

C: You said you would like to write. Do you read a lot? Do you have time for that? T: I have a huge library of books that are in my office that are primarily architecture books, history books. I like to look at imagery of other people’s works. It’s really because I appreciate the beauty of what they have done and respect the amount of hard work it took to get to that. I want to surround myself with books and imagery of great architecture, art and design.

C: Wonderful. T: It’s more of a design library. That’s a happy place on a Saturday with nothing to do. I just go down and flip through these books.

C: And the windows are open and the kids are outside. T: Exactly. Magical day right there.

C: Is there anything you’d like to add? Any string we need to tie up? T: I would just close with the notion that Alys Beach is an amazing place that is going to evolve over the next ten, fifteen, twenty years and beyond, with generations of people who will go there and I feel like I’ll be wandering around there twenty years from now hopefully drinking a margarita and watching kids play and feeling like we had a contribution to make to this amazing place. I think the people at Alys are really wonderful, wonderful, from the family that started it to all the architects that have worked there to all the people who work in the place, let alone the property owners. Everyone I have met there is been so kind and friendly and with a real stunning appreciation for good design, which you don’t find everywhere in the world.

C: It’s great that you’re able to be a part of it and it’s lucky for them. I enjoyed this so much. Thank you.